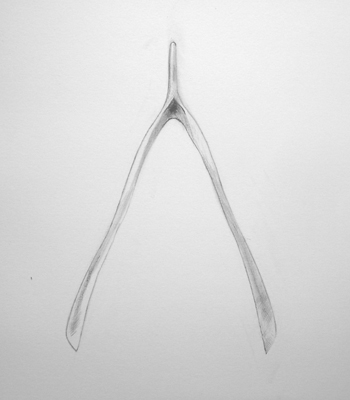

Sketchbook Page 61: Z is for Ziz

January 13, 2015 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 26: Z is for Ziz

This is the twenty-sixth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

The Ziz (Hebrew: זיז) is a giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology, said to be large enough to be able to block out the sun with its wingspan. It is considered to be a giant animal/monster that corresponds to similar archetypal creatures. Rabbis have said that the Ziz is comparable to the Persian Simurgh, while modern scholars compare the Ziz to the Sumerian Anzu and the Ancient Greek Phoenix. Behemoth, Leviathan and Ziz were traditionally a favorite decorative motif for rabbis living in Germany.

There is only passing mention of the Ziz in the Bible, found in Psalms 50:11 “I know all the birds of the mountains and Zīz śāday is mine” and Psalms 80:13-14 “The boar from the forest ravages it, and Zīz śāday feeds on it.” (Hebrew: וְזִ֥יז שָׂ֝דַ֗י), and these are often lost in translation from the Hebrew. The Jewish Aggadah says of the Ziz:As Leviathan is the king of fishes, so the Ziz is appointed to rule over the birds. His name comes from the variety of tastes his flesh has; it tastes like this, zeh, and like that, zeh. The Ziz is as monstrous of size as Leviathan himself. His ankles rest on the earth, and his head reaches to the very sky.

It once happened that travellers on a vessel noticed a bird. As he stood in the water, it merely covered his feet, and his head knocked against the sky. The onlookers thought the water could not have any depth at that point, and they prepared to take a bath there. A heavenly voice warned them: “Alight not here! Once a carpenter’s axe slipped from his hand at this spot, and it took it seven years to touch bottom.” The bird the travelers saw was none other than the Ziz. His wings are so huge that unfurled they darken the sun. They protect the earth against the storms of the south; without their aid the earth would not be able to resist the winds blowing thence. Once an egg of the Ziz fell to the ground and broke. The fluid from it flooded sixty cities, and the shock crushed three hundred cedars. Fortunately such accidents do not occur frequently. As a rule the bird lets her eggs slide gently into her nest. This one mishap was due to the fact that the egg was rotten, and the bird cast it away carelessly.

The Ziz has another name, Renanin, because he is the celestial singer. On account of his relation to the heavenly regions he is also called Sekwi, the seer, and, besides, he is called “son of the nest,” because his fledgling birds break away from the shell without being hatched by the mother bird; they spring directly from the nest, as it were. Like Leviathan, so Ziz is a delicacy to be served to the pious at the end of time, to compensate them for the privations which abstaining from the unclean fowls imposed upon them.

…The creation of the fifth day, the animal world, rules over the celestial spheres. Witness the Ziz, which can darken the sun with its pinions.”

Gentiles also knew of the Ziz. Johannes Buxtorf’s 1603 Synagoga Judaica discusses the Ziz. His text is echoed in English by Samuel Purchas in 1613:

Elias Leuita reporteth of a huge bird, also called Bariuchne, to be rosted at this feast; of which the Talmud saith, that an egge sometime falling out of her nest, did ouerthrow and breake downe three hundred tall Cedars; with which fall the egge being broken, ouerflowed and carried away sixtie Villages… But to take view of other strange creatures, make roome, I pray, for another Rabbi with his Bird; and a great deale of roome you will say is requisite: Rabbi Kimchi on the 50. Psalme auerreth out of Rabbi Iehudah, that Ziz is a bird so great, that with spreading abroad his wings, he hideth the Sunne, and darkeneth all the world. And (to leape back into the Talmud) a certaine Rabbi sayling on the Sea, saw a bird in the middle of the Sea, so high, that the water reached but to her knees; whereupon he wished his companions there to wash, because it was so shallow; Doe it not (saith a voyce from heauen) for it is seuen yeares space since a Hatchet, by chance falling out of a mans hand in this place, and alwayes descending, is not yet come at the bottome.

Humphrey Prideaux in 1698 describes the Ziz as being like a giant celestial rooster:

For in the Tract Bava Bathra of the Babylonish Talmud, we have a Story of such a prodigious Bird, called Ziz, which standing with his Feet upon the Earth, reacheth up unto the Heavens with his head, and with the spreading of his Wings darkneth the whole Orb of the Sun, and causeth a total Eclipse thereof. This Bird the Chaldee Paraphrast on the Psalms says, is a Cock, which he describes of the same bigness, and tells us that he crows before the Lord. And the Chaldee Paraphrast on Job also tells us of him, and of his crowing every morning before the Lord, and that God giveth him Wisdom for this purpose.

Sketchbook Page 60: Y is for Yale

November 3, 2014 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 25: Y is for Yale

This is the twenty-fifth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

The yale or centicore (Latin: eale) is a mythical beast found in European mythology and heraldry. Most descriptions make it an antelope- or goat-like four-legged creature with large horns that it can swivel in any direction.

The name might be derived from Hebrew יָעֵל (yael), meaning “Ibex”.

The yale was first written about by Pliny the Elder in Book VIII of his Natural History. The creature passed into medieval bestiaries and heraldry, where it represents proud defence.

The yale is among the heraldic beasts used by the British Royal Family. It had been used as a supporter for the arms of John, Duke of Bedford, and by England’s House of Beaufort. Its connection with the British monarchy apparently began with Henry VII in 1485. Henry Tudor’s mother, Lady Margaret (1443–1509), was a Beaufort, and the Beaufort heraldic legacy inherited by both her and her son included the yale. Lady Margaret Beaufort was a benefactor of Cambridge’s Christ’s College and St John’s College and her yale supporters can be seen on the college gates. There are also yales on the roof of St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle. The Yale of Beaufort was one of the Queen’s Beasts commissioned for the coronation in 1953; the plaster originals are in Canada, stone copies are at Kew Gardens, outside the palm house.

In the US, the yale as a heraldic symbol is weakly associated with Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Neither the University’s coat of arms nor most of its other heraldry features the yale, and the school’s primary sports mascot is a bulldog named Handsome Dan. But a yale is depicted on the official banner of the President of the University, which is carried and displayed during commencement exercises each spring, and yales can be seen above the gateway to Yale’s Davenport College and the pediment of Timothy Dwight College. The student-run campus radio station, WYBCX Yale Radio, uses the yale as its logo.

Sketchbook Page 59: X is for Xing Tian

September 1, 2014 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 24: X is for Xing Tian

This is the twenty-fourth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

Xing Tian (Chinese: 刑天; pinyin: Xíngtiān) is a notable deity of Chinese mythology who fights against the Supreme Divinity, (sometimes known as Tian), not giving up even after the event of his decapitation. Losing the fight for supremacy, he was beheaded and his head buried in Changyang Mountain. Nevertheless, headless, with a shield in one hand and a battle ax in the other, he continues the fight; using his nipples for eyes and his bellybutton for a mouth.

Xing Tian is encountered in chapter 7 of the Shanhaijing (a Chinese classic text and a compilation of early geography and myth) as well as in subsequent works, such as a poem by Tao Yuanming (367-427 CE). In the history Lushi compiled by Luo Mi, Xing Tian is described as a minister of Yan Di, who composed music for farmers for plowing and harvesting, however this Xing Tian is written with a different character for Xing, so it is unclear whether the two represent the same figure.

The following excerpt is from the Shanhaijing:

刑天與帝爭神,帝斷其首,葬之常羊之山,乃以乳為目,以臍為口,操干戚以舞。

Roughly translated:

Xing Tian fought against [Huang] Di. Di cut off his head, and the head was buried in the Changyang Mountains. But Xing Tian, with his breasts as eyes, and his navel as mouth, continued to fight with his axe and shield.

According to oracle bones, during ancient times the giant Xíng Tiān was originally a follower of the Emperor Yán. After the victory of the Yellow Emperor over Yán at the Battle of Banquan, Xíng Tiān followed his master to exile in the south. At this time, the giant had no name.

After the Yellow Emperor defeated and executed Chi You, Xíng Tiān went forth with an axe and shield (some descriptions gave a blade instead) against the Yellow Emperor. He forced his way to the southern Gate of the Celestial Court and issued a challenge to the Yellow Emperor for a duel.

The Yellow Emperor came forth and the two engaged in a ferocious combat, sword (昆吾剑) against axe, all the way down to earth to ChángYáng Mountain (常羊之山). In a final blow, the Yellow Emperor distracted his opponent with a trick and lunged … and in a flash decapitated Xíng Tiān, whose head rolled all the way to the foot of the mountain and created a thunderous roar.

Instead of dying, Xíng Tiān was able to continue moving and began groping about for his head. The Yellow Emperor raised his sword to strike the mountain. The mountain split open, the head rolled within and the mountain closed again.

Xíng Tiān gave up looking for his head, and instead used his nipples as eyes that could not see, and navel as a mouth that could not open. He began striking about wildly, giving rise to the saying “刑天舞干戚,猛志固常在” (undying resolution). Thereafter, the headless giant got his name, which meant “He whose head was chopped off”.

Xingtian symbolizes the indomitable spirit which never surrenders and maintains the will to resist no matter what tribulations one may undergo or what troubles one may face (if the word face can be used in this case).

Sketchbook Page 58: W is for Wolpertinger

August 25, 2014 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 23: W is for Wolpertinger

This is the twenty-third in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

Bavarian folklore tells of the Wolpertinger (also called Wolperdinger, Poontinger or Woiperdinger), a mythological hybrid animal allegedly inhabiting the alpine forests of Bavaria in Germany.

It has a body comprised from various animal parts — generally wings, antlers, tails and fangs, all attached to the body of a small mammal. The most widespread description portrays the Wolpertinger as having the head of a rabbit, the body of a squirrel, the antlers of a deer, and the wings and — occasionally — legs of a pheasant.

Stuffed “Wolpertingers”, composed of parts of actual stuffed animals, are often displayed in inns or sold to tourists as souvenirs in the animals’ “native regions”. The Deutsches Jagd- und Fischereimuseum in Munich, Germany features a permanent exhibit on the creature.

It resembles other creatures from German folklore, such as the Rasselbock of the Thuringian Forest, or the Elwedritsche of the Palatinate region, which accounts describe as a chicken-like creature with antlers; additionally the American Jackalope as well as the Swedish Skvader somewhat resemble the Wolpertinger. The Austrian counterpart of the Wolpertinger is the Raurakl.

Sketchbook Page 57: V is for Vānara

August 4, 2014 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 22: V is for Vānara

This is the twenty-second in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

Vānara (Sanskrit: वानर) refers to a group of ape-like humanoids or monkeys in the Hindu epic Ramayana and its various versions. In Ramayana, the Vanaras help Rama defeat Ravana. The Vanaras also appear in other texts, including Mahabharata.

There are three main theories about the etymology of the word “Vanara”:

- It derives from the word vana (“forest”), and means “belonging to the forest” or “forest-dwelling”.

- It derives from the words vana (“forest”) and nara (“man”), thus meaning “forest man”.

- It derives from the words vav and nara, meaning “is it a man?” or “perhaps he is man”.

Although the word Vanara has come to mean “monkey” over the years and the Vanaras are depicted as monkeys in popular art, their exact identity is not clear. Unlike other exotic creatures, such as the rakshasas, the Vanaras do not have a precursor in the Vedic literature. The Ramayana presents them as humans with reference to their speech, clothing, habitations, funerals, consecrations etc. It also describes their ape-like characteristics such as their prowess at leaping, their hair, their fur and a tail.

According to one theory, the Vanaras are strictly mythological creatures. This is based on their supernatural abilities, as well as written descriptions of Brahma commanding other deities to either bear Vanara offspring or to incarnate as Vanaras to help Rama in his mission. The Jain re-tellings of Ramayana describe them as a clan of supernatural beings called the Vidyadharas; the flag of this clan bears monkeys as emblems.

Another theory identifies the Vanaras with tribal people who dwelled in the forests and used monkey totems. G. Ramdas, based on Ravana’s reference to the Vanaras’ tail as an ornament, infers that the “tail” was actually an appendage in the dress worn by the men of the Savara tribe (The female Vanaras are not described as having a tail). According to this theory, the non-human characteristics of the Vanaras may be considered a product of artistic imagination. In Sri Lanka, the word “Vanara” has been used to describe the Nittaewos mentioned in the Vedic legends.

Vanaras were created by Brahma and other gods to help Rama in battle against Ravana. They are powerful and have many godly traits. Taking Brahma’s orders, the gods began to parent sons in the semblance of monkeys (Ramayana 1.17.8). The Vanaras took birth in bears and monkeys, subsequently attaining the shape and valor of the gods and goddesses who created them (Ramayana 1.17.17-18). After Vanaras were created they began to organise themselves into armies and spread across the forests; although some, including Vali, Sugriva, and Hanuman, stayed near mount Riskshavat.

According to the Ramayana, the Vanaras lived primarily in the region of Kishkindha (identified with parts of the present-day Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh & Maharashtra). Rama first met them in Dandaka Forest, during his search for Sita. An army of Vanaras helped Rama in his search for Sita, and also in battle against Ravana, Sita’s abductor. It is Nala and Nila who built a bridge over the ocean so that Rama and his army could cross to Lanka. As described in the epic, the characteristics of the Vanara are described as amusing, childish, mildly irritating, badgering, hyperactive, adventurous, bluntly honest, loyal, courageous, and kind.

In the Ramayana, the Vanara Hanuman changes shape several times. For example, while he searches for the kidnapped Sita in Ravana’s palaces on Lanka, he contracts himself to the size of a cat, so that he will not be detected by the enemy. Later on he takes on the size of a mountain, blazing with radiance, to show his true power to Sita.

Sketchbook Page 26 (revisited): U is for Unicorn

May 13, 2014 § Leave a comment

Monoceros (burial)

Bones from a Bestiary part 21: U is for Unicorn

This is the twenty-first in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

The unicorn is a legendary animal that has been described since antiquity as a beast with a large, pointed, spiralling horn projecting from its forehead. The unicorn was depicted in ancient seals of the Indus Valley Civilization and was mentioned by the ancient Greeks in accounts of natural history by various writers, including Ctesias, Strabo, Pliny the Younger, and Aelian. The Bible also describes an animal, the re’em, which some translations have rendered with the word unicorn.

In European folklore, the unicorn is often depicted as a white horselike or goatlike animal with a long horn and cloven hooves (sometimes with a goat’s beard). In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, it was commonly described as an extremely wild woodland creature, a symbol of purity and grace, which could only be captured by a virgin. In the encyclopedias its horn was said to have the power to render poisoned water potable and to heal sickness. In medieval and Renaissance times, the horn of the narwhal was sometimes sold as unicorn horn.

Unicorns are not found in Greek mythology, but rather in accounts of natural history, for Greek writers of natural history were convinced of the reality of the unicorn, which they located in India, a distant and fabulous realm for them. The earliest description is from Ctesias who, in his book Indika (“On India”), described them as wild asses, fleet of foot, having a horn a cubit and a half (27 inches) in length, and colored white, red and black. Aristotle must be following Ctesias when he mentions two one-horned animals, the oryx (a kind of antelope) and the so-called “Indian ass”. Strabo says that in the Caucasus there were one-horned horses with stag-like heads. Pliny the Elder mentions the oryx and an Indian ox (perhaps a rhinoceros) as one-horned beasts, as well as:

“a very fierce animal called the monoceros which has the head of the stag, the feet of the elephant, and the tail of the boar, while the rest of the body is like that of the horse; it makes a deep lowing noise, and has a single black horn, which projects from the middle of its forehead, two cubits in length.”

In On the Nature of Animals (Περὶ Ζῴων Ἰδιότητος, De natura animalium), Aelian, quoting Ctesias, adds that India produces also a one-horned horse (iii. 41; iv. 52), and says (xvi. 20) that the monoceros (Greek:μονόκερως) was sometimes called cartazonos (Greek: καρτάζωνος), which may be a form of the Arabic karkadann, meaning “rhinoceros”.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a merchant of Alexandria who lived in the 6th century, made a voyage to India and subsequently wrote works on cosmography. He gives a description of a unicorn based on four brass figures in the palace of the King of Ethiopia. He states, from report, that:

“it is impossible to take this ferocious beast alive; and that all its strength lies in its horn. When it finds itself pursued and in danger of capture, it throws itself from a precipice, and turns so aptly in falling, that it receives all the shock upon the horn, and so escapes safe and sound.”

A one-horned animal (which may be just a bull in profile) is found on some seals from the Indus Valley Civilization. Seals with such a design are thought to be a mark of high social rank.

Medieval knowledge of the fabulous beast stemmed from biblical and ancient sources, and the creature was variously represented as a kind of wild ass, goat, or horse.

The predecessor of the medieval bestiary, compiled in Late Antiquity and known as Physiologus (Φυσιολόγος), popularised an elaborate allegory in which a unicorn, trapped by a maiden (representing the Virgin Mary), stood for the Incarnation. As soon as the unicorn sees her, it lays its head on her lap and falls asleep. This became a basic emblematic tag that underlies medieval notions of the unicorn, justifying its appearance in every form of religious art. Interpretations of the unicorn myth focus on the medieval lore of beguiled lovers, whereas some religious writers interpret the unicorn and its death as the Passion of Christ. The myths refer to a beast with one horn that can only be tamed by a virgin; subsequently, some writers translated this into an allegory for Christ’s relationship with the Virgin Mary.

The unicorn also figured in courtly terms: for some 13th century French authors such as Thibaut of Champagne and Richard de Fournival, the lover is attracted to his lady as the unicorn is to the virgin. With the rise of humanism, the unicorn also acquired more orthodox secular meanings, emblematic of chaste love and faithful marriage. It plays this role in Petrarch’s Triumph of Chastity, and on the reverse of Piero della Francesca’s portrait of Battista Strozzi, paired with that of her husband Federico da Montefeltro (painted c 1472-74), Bianca’s triumphal car is drawn by a pair of unicorns.

The Throne Chair of Denmark is made of “unicorn horns” – almost certainly narwhal tusks. The same material was used for ceremonial cups because the unicorn’s horn continued to be believed to neutralize poison, following classical authors.

The unicorn, tamable only by a virgin woman, was well established in medieval lore by the time Marco Polo described them as:

“scarcely smaller than elephants. They have the hair of a buffalo and feet like an elephant’s. They have a single large black horn in the middle of the forehead… They have a head like a wild boar’s… They spend their time by preference wallowing in mud and slime. They are very ugly brutes to look at. They are not at all such as we describe them when we relate that they let themselves be captured by virgins, but clean contrary to our notions.“

It is clear that Marco Polo was describing a rhinoceros. In German, since the 16th century, Einhorn (“one-horn”) has become a descriptor of the various species of rhinoceros.

One traditional method of hunting unicorns involved entrapment by a virgin.

In one of his notebooks Leonardo da Vinci wrote:

The unicorn, through its intemperance and not knowing how to control itself, for the love it bears to fair maidens forgets its ferocity and wildness; and laying aside all fear it will go up to a seated damsel and go to sleep in her lap, and thus the hunters take it.

The famous late Gothic series of seven tapestry hangings The Hunt of the Unicorn are a high point in European tapestry manufacture, combining both secular and religious themes. The tapestries now hang in the Cloisters division of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. In the series, richly dressed noblemen, accompanied by huntsmen and hounds, pursue a unicorn against mille-fleur backgrounds or settings of buildings and gardens. They bring the animal to bay with the help of a maiden who traps it with her charms, appear to kill it, and bring it back to a castle; in the last and most famous panel, “The Unicorn in Captivity,” the unicorn is shown alive again and happy, chained to a pomegranate tree surrounded by a fence, in a field of flowers. Scholars conjecture that the red stains on its flanks are not blood but rather the juice from pomegranates, which were a symbol of fertility. However, the true meaning of the mysterious resurrected Unicorn in the last panel is unclear. The series was woven about 1500 in the Low Countries, probably Brussels or Liège, for an unknown patron. A set of six engravings on the same theme, treated rather differently, were engraved by the French artist Jean Duvet in the 1540s.

The Unicorn Is Penned, Unicorn Tapestries, c. 1495–1505 (The Cloisters, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC)

A rather rare, late 15th century, variant depiction of the hortus conclusus in religious art combined the Annunciation to Mary with the themes of the Hunt of the Unicorn and Virgin and Unicorn, so popular in secular art. The unicorn already functioned as a symbol of the Incarnation and whether this meaning is intended in many prima facie secular depictions can be a difficult matter of scholarly interpretation. There is no such ambiguity in the scenes where the archangel Gabriel is shown blowing a horn, as hounds chase the unicorn into the Virgin’s arms, and a little Christ Child descends on rays of light from God the Father. The Council of Trent finally banned this somewhat over-elaborated, if charming, depiction, partly on the grounds of realism, as no one now believed the unicorn to be a real animal.

Shakespeare scholars describe unicorns being captured by a hunter standing in front of a tree, the unicorn goaded into charging; the hunter would step aside the last moment and the unicorn would embed its horn deeply into the tree: as per this line from Timon of Athens, Act 4, scene 3, c. line 341:

“wert thou the unicorn, pride and wrath would confound thee and make thine own self the conquest of thy fury”

Sketchbook Page 56: T is for Titan

May 8, 2014 § 1 Comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 20: T is for Titan

This is the twentieth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

In Greek mythology, the Titans (Greek: Τιτάν—Ti-tan; plural: Τιτᾶνες—Ti-tânes) were a primeval race of powerful deities, descendants of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky), that ruled during the legendary Golden Age. They were immortal giants of incredible strength and were also the first pantheon of Greek gods and goddesses.

In the first generation of twelve Titans, the males were Oceanus, Hyperion, Coeus, Cronus, Crius, and Iapetus and the females—the Titanesses or Titanides—were Mnemosyne, Tethys, Theia, Phoebe, Rhea, and Themis. The second generation of Titans consisted of Hyperion’s children Helios, Selene and Eos; Coeus’s daughters Leto and Asteria; Iapetus’s children Atlas, Prometheus, Epimetheus, and Menoetius; Oceanus’ daughter Metis; and Crius’ sons Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.

The Titans were overthrown by a race of younger gods, the Olympians, in the Titanomachy (“War of the Titans”). The Greeks may have borrowed this mytheme from the Ancient Near East.

Greeks of the classical age knew of several poems about the war between the Olympians and Titans. The dominant one, and the only one that has survived, was in the Theogony attributed to Hesiod. A lost epic, Titanomachia—attributed to the legendary blind Thracian bard Thamyris—was mentioned in passing in an essay On Music that was once attributed to Plutarch. The Titans also played a prominent role in the poems attributed to Orpheus. Although only scraps of the Orphic narratives survive, they show interesting differences with the Hesiodic tradition.

The Greek myths of the Titanomachy fall into a class of similar myths throughout Europe and the Near East concerning a war in heaven, where one generation or group of gods largely opposes the dominant one. Sometimes the elders are supplanted, and sometimes the rebels lose and are either cast out of power entirely or incorporated into the pantheon. Other examples might include the wars of the Æsir with the Vanir and Jotuns in Scandinavian mythology, the Babylonian epic Enuma Elish, the Hittite “Kingship in Heaven” narrative, the obscure generational conflict in Ugaritic fragments, Virabhadra’s conquest of the early Vedic Gods, and the rebellion of Lucifer in Christianity. The Titanomachy lasted for ten years.

Another myth concerning the Titans that is not in Hesiod revolves around Dionysus. At some point in his reign, Zeus decides to give up the throne in favor of the infant Dionysus, who like the infant Zeus is guarded by the Kouretes. The Titans decide to slay the child and claim the throne for themselves; they paint their faces white with gypsum, distract Dionysus with toys, then dismember him and boil and roast his limbs. Zeus, enraged, slays the Titans with his thunderbolt; Athena preserves the heart in a gypsum doll, out of which a new Dionysus is made. This story is told by the poets Callimachus and Nonnus, who call this Dionysus “Zagreus”, and in a number of Orphic texts, which do not.

One iteration of this story, that of the Late Antique Neoplatonist philosopher Olympiodorus, recounted in his commentary of Plato’s Phaedrus, affirms that humanity sprang up out of the fatty smoke of the burning Titan corpses. Pindar, Plato and Oppian refer offhandedly to man’s “Titanic nature”. According to them, the body is the titanic part, while soul is the divine part of man. Other early writers imply that humanity was born out of the malevolent blood shed by the Titans in their war against Zeus. Some scholars consider that Olympiodorus’ report, the only surviving explicit expression of this mythic connection, embodied a tradition that dated to the Bronze Age, while Radcliffe Edmonds has suggested an element of innovative, allegorical improvisation to suit Olympiodorus’ purpose.

Some scholars of the past century or so, including Jane Ellen Harrison, have argued that an initiatory or shamanic ritual underlies the myth of Dionysus’ dismemberment and cannibalism by the Titans. She also asserts that the word “Titan” comes from the Greek τιτανος, signifying white earth, clay or gypsum, and that the Titans were “white clay men”, or men covered by white clay or gypsum dust in their rituals. M.L. West also asserts this in relation to the shamanistic initiatory rites of early Greek religious practices.

According to Paul Faure, the name “Titan” can be found in Linear A (one of the ancient Cretan writing systems) written as “Tan” or “Ttan”, which represents a single deity rather than a group. Other scholars believe the word is related to the Greek verb τείνω (to stretch), a view Hesiod himself appears to share:

“But their father Ouranos, who himself begot them, bitterly gave to them to those others, his sons, the name of Titans, the Stretchers, for they stretched out their power outrageously.”

Sketchbook Page 55: S is for Selkie

May 4, 2014 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 19: S is for Selkie

This is the nineteenth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

Selkies (also spelled silkies, selchies; Irish/Scottish Gaelic: selchidh, Scots: selkie fowk) are mythological creatures found in Scottish,Irish, and Faroese folklore. Similar creatures are described in the Icelandic traditions. The word derives from earlier Scots selich, (from Old English seolh meaning seal). Selkies are said to live as seals in the sea but shed their skin to become human on land. The legend is apparently most common in Orkney and Shetland and is very similar to those of swan maidens.

Male selkies are described as being very handsome in their human form, and having great seductive powers over human women. They typically seek those who are dissatisfied with their life, such as married women waiting for their fishermen husbands. If a woman wishes to make contact with a selkie male, she must shed seven tears into the sea. If a man steals a female selkie’s skin she is in his power and is forced to become his wife. Female selkies are sometimes willing to accept this role, but because their true home is the sea, they will often be seen gazing longingly at the ocean. If she finds her skin she will immediately return to her true home, and sometimes to her selkie husband, in the sea. Sometimes, a selkie maiden is taken as a wife by a human man and will have several children by him. In these stories, it is one of her children who discovers her sealskin (often unwitting of its significance) and she soon returns to the sea. The selkie woman usually avoids seeing her human husband again but is sometimes shown visiting her children and playing with them in the waves.

Stories concerning selkies are generally romantic tragedies. Sometimes the human will not know that their lover is a selkie, and wakes to find them gone. In other stories the human will hide the selkie’s skin, thus preventing it from returning to its seal form. A selkie can only make contact with one human for a short amount of time before they must return to the sea. They are unable to make contact with that human again for seven years, unless the human steals their selkie skin and hides it or burns it.

In the Faroe Islands there are two versions of the story of the Selkie or Seal Wife. A young farmer from the town of Mikladalur on Kalsoy island goes to the beach to watch the selkies dance. He hides the skin of a beautiful selkie maid, so she cannot go back to sea, and forces her to marry him. He keeps her skin in a chest, and keeps the key with him both day and night. One day when out fishing, he discovers that he has forgotten to bring his key. When he returns home, the selkie wife has escaped back to sea, leaving their children behind. Later, when the farmer is out on a hunt, he kills both her selkie husband and two selkie sons, and she promises to take revenge upon the men of Mikladalur. Some shall be drowned, some shall fall from cliffs and slopes, and this shall continue, until so many men have been lost that they will be able to link arms around the whole island of Kalsoy.

Selkies are not always faithless lovers. Peter Cagan and the Wind by Gordon Bok tells of the fisherman Cagan who married a seal-woman. Against his wife’s wishes he set sail dangerously late in the year, and was trapped battling a terrible storm, unable to return home. His wife shifted to her seal form and saved him, even though this meant she could never return to her human body and hence her happy home.

Some stories from Shetland have selkies luring islanders into the sea at midsummer, the lovelorn humans never returning to dry land.

A legend similar to that of the selkie is also told in Wales, but in a slightly different form. The selkies are humans who have returned to the sea. Dylan (Dylan ail Don) the firstborn of Arianrhod, was variously a merman or sea spirit, who in some versions of the story escapes to the sea immediately after birth.

Seal shapeshifters similar to the selkie exist in the folklore of many cultures. A corresponding creature existed in Swedish legend, and the Chinook people of North America have a similar tale of a boy who changes into a seal.

Before the advent of modern medicine many physiological conditions were untreatable and when children were born with abnormalities it was common to blame the fairies. The MacCodrum clan of the Outer Hebrides became known as the “MacCodrums of the seals” as they claimed to be descended from a union between a fisherman and a selkie as an explanation for the hereditary horny growth between their fingers that made their hands resemble flippers. Scottish folklorist and antiquarian, David MacRitchie believed that early settlers in Scotland probably encountered, and even married, Finnish and Saami women who were misidentified as selkies because of their sealskin kayaks and clothing. Others have suggested that the traditions concerning the selkies may have been due to misinterpreted sightings of the Saami people. The Saami wore clothes and used kayaks, both made of animal skins. Both the clothes and kayaks would lose buoyancy when saturated and would need to be dried out. It is thought that sightings of Saami divesting themselves of their clothing or lying next to the skins on the rocks could have led to the belief in their ability to change from a seal to a man.

Another belief is that shipwrecked Spaniards were washed ashore and their jet black hair resembled seals. As the anthropologist A. Asbjorn Jon has recognised though, there is a strong body of lore that indicates that selkies “are said to be supernaturally formed from the souls of drowned people”.

Sketchbook Page 54: R is for Ratatoskr

March 26, 2014 § Leave a comment

Bones from a Bestiary part 18: R is for Ratatoskr

This is the eighteenth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

In Norse mythology, Ratatoskr (Old Norse, generally considered to mean “drill-tooth”or “bore-tooth”) is a squirrel who runs up and down the world tree Yggdrasil to carry messages between the eagle Hræsvelgr, perched atop Yggdrasil, and the wyrm Níðhöggr, who dwells beneath one of the three roots of the tree. Sometimes pictured with a horn on his head, Ratatoskr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the squirrel.

Ratatoskr climbing Yggdrasil. The text by the animal reads “Rata / tøskur / ber øf / undar / ord my / llū arnr / og nyd / hoggs”. From a 17th century Icelandic manuscript now in the care of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland.

The name Ratatoskr contains two elements: rata- and -toskr. The element toskr is generally held to mean “tusk”. Guðbrandur Vigfússon theorized that the rati- element means “the traveller”. He says that the name of the legendary drill Rati may feature the same term. According to Vigfússon, Ratatoskr means “tusk the traveller” or “the climber tusk.”

Sophus Bugge theorised that the name Ratatoskr is a loan from Old English meaning “Rat-tooth.” Bugge’s hypothesis hinges on the fact that the -toskr element of the compound does not appear anywhere else in Old Norse. Bugge proposed that the -toskr element is a reformation of the Old English word tūsc (Old Frisian tusk) and, in turn, that the element Rata- represents Old English ræt (“rat”). According to Albert Sturtevant, “[as] far as the element Rata- is concerned, Bugge’s hypothesis has no valid foundation in view of the fact that the [Old Norse] word Rata (gen. form of Rati) is used in Háv[amál] (106, 1) to signify the instrument which Odin employed for boring his way through the rocks in quest of the poet’s mead […]” and that “Rati must then be considered a native [Old Norse] word meaning “The Borer, Gnawer” […]”. Sturtevant says that Bugge’s theory regarding the element -toskr may appear to be supported by the fact that the word does not appear elsewhere in Old Norse. Sturtevant, however, disagrees. Sturtevant says that the Old Norse proper name Tunne (derived from Proto-Norse Tunþē) refers to “a person who is characterized as having some peculiar sort of tooth” and theorizes a Proto-Germanic form of -toskr. Sturtevant concludes that “the fact that the [Old Norse] word occurs only in the name Rata-toskr is no valid evidence against this assumption, for there are many [Old Norse] hapax legomena of native origin, as is attested by the equivalents in the Mod[ern]

In the Poetic Edda poem Grímnismál, the god Odin (disguised as Grímnir) says that Ratatoskr runs up and down Yggdrasil bringing messages between the eagle perched atop it and Níðhöggr below it.

Henry Adams Bellows’ translation reads thus:

Ratatosk is the squirrel who there shall run

On the ash-tree Yggdrasil;

From above the words of the eagle he bears,

And tells them to Nithhogg beneath.

Ratatoskr is described in the Prose Edda’s Gylfaginning’s chapter 16, in which High (a pseudonym for Odin) states that:

‘An eagle sits at the top of the ash, and it has knowledge of many things. Between its eyes sits the hawk called Vedrfolnir […]. The squirrel called Ratatosk […] runs up and down the ash. He tells slanderous gossip, provoking the eagle and Nidhogg.’

According to Rudolf Simek, “the squirrel probably only represents an embellishing detail to the mythological picture of the world-ash in Grímnismál.” Hilda Ellis Davidson, describing the world tree, states the squirrel is said to gnaw at it — furthering a continual destruction and re-growth cycle, and posits the tree symbolizes ever-changing existence. John Lindow points out that Yggdrasil is described as rotting on one side and as being chewed on by four harts and Níðhöggr, and that, according to the account in Gylfaginning, it also bears verbal hostility in the fauna it supports. Lindow adds that “in the sagas, a person who helps stir up or keep feuds alive by ferrying words of malice between the participants is seldom one of high status, which may explain the assignment of this role in the mythology to a relatively insignificant animal.”

Richard W. Thorington Jr. and Katie Ferrell theorize that “the role of Ratatosk probably derived from the habit of European tree squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) to give a scolding alarm call in response to danger. It takes little imagination for you to think that the squirrel is saying nasty things about you.” Modern scholars have accepted this etymology, listing the name Ratatoskr as meaning “drill-tooth” (Jesse Byock, Andy Orchard, Rudolf Simek) or “bore-tooth” (John Lindow).

Sketchbook Page 53: Q is for Quinotaur

February 2, 2014 § 2 Comments

Bones from a Bestiary part 17: Q is for Quinotaur

This is the seventeenth in a series of chimerical creatures; the aim is to create an alphabet of fabulous beasts over the coming months.

With recent advances in genetic engineering it should be possible to manufacture such creatures in the laboratory; although the results will not always be practical (or, indeed, humane) …

The Quinotaur (Lat. Quinotaurus) is a mythical sea creature mentioned in the 7th century Frankish Chronicle of Fredegar. Referred to as “bestea Neptuni Quinotauri similes“, (the beast of Neptune which resembles a Quinotaur) it was held to have fathered Meroveus by attacking the wife of the Frankish king Chlodio and thus to have sired the line of Merovingian kings.

The name translates from Latin as “bull with five horns”, whose attributes have commonly been interpreted as the incorporated symbols of the sea-god Neptune with his trident, and the horns of a mythical bull or Minotaur.

It is not known whether the legend merged both elements by itself or whether this merger should be attributed to the Christian author. The clerical Latinity of the name does not indicate whether it is a translation of some genuine Frankish creature or a coining.

The mythological assault, and subsequent family relation, of this monster attributed to Frankish mythology correspond to both the Indo-European etymology of Neptune (from PIE ‘*nepots’, “grandson” or “nephew”, compare also the Indo-Aryan ‘Apam Napat’, “grandson/nephew of the water”) and to bull-related fertility myths in Greek mythology, where for example the Phoenician princess Europa was abducted by the god Zeus, in the form of a white bull, that swam her away to Crete.